Born and raised in Asia, I had my first job in Singapore for a US company under a French boss. After a couple of years, I changed to a French company but managed the APAC business including Japan, Korea and South East Asia markets. Recently moved to the states, I started to experience a lot more about the different side of the world too. The international companies that I was in, gave me huge exposure to different culture and style. I made a lot of mistakes, but grew significantly as well.

Culture Map

One day, my boss suddenly told me secretly that he had sent me a gift, saying that he thought of me a few times when looking at the gift. A few days later, I received a book called “The Culture Map.” During a business trip, I opened this book and read through many chapters. Finally, I understood why he said he would think of me when he saw this book. He deeply understood the challenges I faced while managing the Japanese market at that time.

Every country has its unique culture, and without understanding the distinct cultures of different countries, you may find yourself confused in situations where you have no idea why things go wrong. The author of “The Culture Map,” Erin Meyer, conducted an extensive survey of middle managers in each country and categorized her research into these eight dimensions:

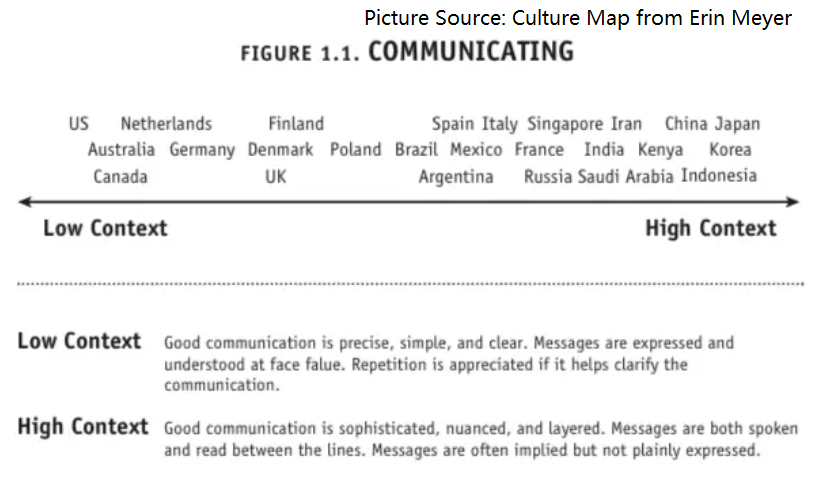

- Communication styles: Low vs. High contextual

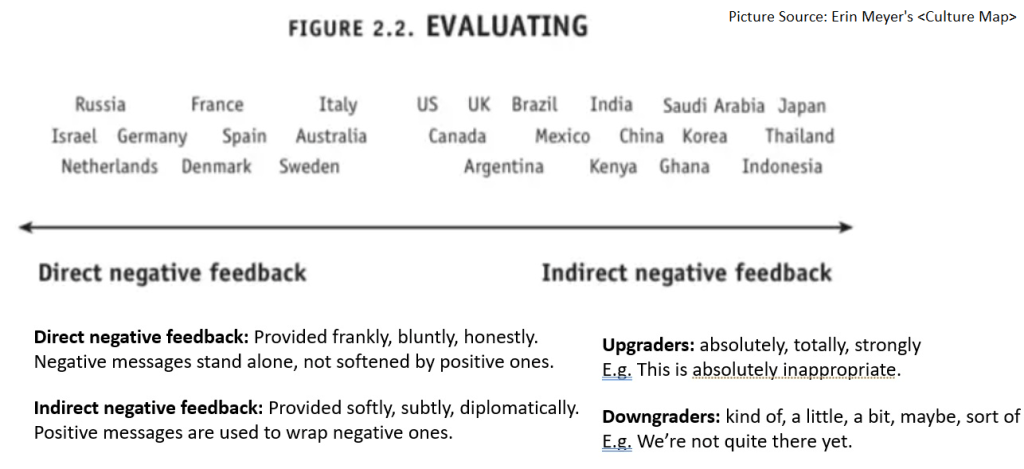

- Negative feedback styles: Direct vs. Indirect feedback

- Persuasion approaches: Principle first vs. Application first

- Leadership styles: Egalitarian vs. Hierarchical

- Decision-making processes: Consensus vs. Top Down

- Trust-building methods: Task based vs. Relationship based

- Conflict resolution strategies: Confrontational vs. Avoiding conflicts

- Time management and punctuality expectations: Fixed vs. Flexible

By exploring these dimensions, Meyer provides valuable insights and guidance for navigating cross-cultural interactions and avoiding misunderstandings in a globalized world.

Each country corresponds to a value on these sales. However, at an individual level, everyone is unique. Our work styles are also influenced by our upbringing, education, and first job, as well as the colleagues we interacted with. The values on these dimensions represent the predominant tendencies, but they do not necessarily apply to every person.

It’s important to remember that while cultural norms provide a framework for understanding and interacting with others, individuals within a culture can still exhibit variations and deviations from those norms. Recognizing and respecting individual differences is crucial in effective cross-cultural communication and collaboration.

Communication Styles

For example: The United States is known for having a low-context culture, where communication is typically straightforward and literal. In contrast to Asian countries like China and Japan, the United States is a melting pot of cultures. If there are hidden meanings or implications in a conversation, it can be difficult for individuals from other cultures to understand and communicate effectively. The American education system highly values clear and direct communication, where being able to express anything clearly and explicitly is seen as a sign of effective communication. There’s no need for beating around the bush or guessing.

On the other hand, in Asian cultures, such as China and Japan, which have deep-rooted history and shared ways of thinking, there are certain things that people are not comfortable expressing directly. Instead, they may use indirect communication, hints, and non-verbal cues to convey deeper messages. Being too direct and explicit can sometimes be seen as rude. For example, when receiving a gift, it is common in many instances for people to initially refuse it multiple times before accepting it, as accepting it immediately might be perceived as impolite. I have personally witnessed many times where my grandmother almost getting into an argument/physical fights with guests while trying to return a gift when someone insisted on giving it to her. (It’s not polite to accept gift directly.) This kind of behavior would be completely misunderstood by foreigners.

Having worked in an international company, I have had the privilege of collaborating with colleagues from various countries. When working with colleagues from Southeast Asian countries, since everyone comes from different nations, there is active participation and sharing of challenges and accomplishments during meetings. I have learned a lot from them. However, when I started working with Japanese colleagues, I was surprised that a meeting scheduled for one hour would often finished in less than half an hour. Each person would only speak a few sentences. I found it a bit awkward because it was challenging to understand what specifically was discussed. It was only after reading this book that everything became clear to me.

During meetings, Japanese colleagues would listen attentively, afraid of missing any implicit messages conveyed by the boss. However, in an international meeting, if you speak with someone from a low-context culture, they might just interpret your words at face value, while someone from a high-context culture may associate various hidden meanings, potentially leading to misunderstandings. It can easily result in unintended consequences, with the speaker being unaware and the listener reading into something that was not intended.

In Japan, they have coined a term called “KY,” which refers to people who cannot understand the unspoken implications. Their meetings are simple and implicit, without taking up extra time. However, for those of us who are not familiar with their culture, it can be really difficult to extract any meaningful information from those meetings. After working in the Japanese market for over two years, I deeply resonate with this experience. Looking back, I realize that many times I was that “KY” person.

Recently, I have been focusing on the American market, and it has made me realize the significant differences in communication. Whenever I don’t understand something, my American colleagues patiently explain it to me multiple times and allow me to ask questions and clarify doubts. Often, low-context conversations can greatly facilitate smooth communication.

Furthermore, I have also discovered that when I have become accustomed to communicating in a low-context manner, if I use the same approach when speaking with individuals from high-context cultures, it often leads to unintended consequences. Once, while communicating with a Chinese executive, I suddenly noticed that there were occasional misunderstanding in our conversation. For instance, when I asked a few extra questions simply because I wanted to understand why certain situations occurred, it could easily be interpreted as a lack of trust, especially when we share the same ethnicity and appearance, leading to the assumption that we would interpret things in the same way. After reading “The Culture Map,” I gained a better understanding of the underlying reasons and realized the need to adjust my communication strategies.

Again, our communication styles are not solely determined by our upbringing but can also be influenced by our university environment, first job experience, and various other factors.

Which of the following situations do you think would have the most communication issues?

- Two individuals from low-context cultures.

- Two individuals from different high-context cultures.

- One individual from a low-context culture and one individual from a high-context culture.

Many people might assume that the combination in 3) would result in the greatest communication problems, but in reality, it is 2). Low-context communication tends to clarify issues clearly and unambiguously, whereas if both parties are from high-context cultures where there are hidden meanings, the misunderstandings can grow.

Therefore, if you are dealing with individuals from high-context cultures while coming from a low-context culture, the following strategies can be helpful:

- Listen attentively and try to understand what others may be implying, rather than just focusing on the literal meaning of their words.

- Seek clarification and openly acknowledge your lack of knowledge about certain cultural aspects, which may require asking many questions to gain a better understanding.

On the other hand, if you are dealing with individuals from low-context cultures while coming from a high-context culture, the following strategies can be useful:

- Strive for transparency and specificity, and after meetings, summarize and share the discussed content to ensure there are no misunderstandings. Repetition is also acceptable.

- Be aware of any unexpressed expectations you may have.

- Sometimes, it may not be necessary to be overly polite, and you can directly express your needs.

Negative Feedback Style

Furthermore, it is interesting that while Americans strive to communicate clearly and explicitly, they tend to be extremely indirect when giving negative feedback.

My American colleagues, when providing feedback, usually focus on positive and constructive remarks, rarely pointing out areas for improvement. Even if there are areas to address, they tend to mix them in with positive feedback, making it appear less critical.

This aspect is similar to my Japanese colleagues. During year-end evaluations, even if I know that some colleagues have concerns or suggestions about others or projects, I hardly see any direct recommendations. This situation often leaves me perplexed because I was aware of the issues, but if the individuals involved didn’t bring them up directly, I found myself in a dilemma as an intermediary.

The same applies to my Chinese colleagues. Once, the leader of a Chinese project team I was part of was dissatisfied with the work done by the American team, but the Chinese leader refrained from addressing it directly. I discussed this with my French boss, and he agreed that I should communicate this feedback to the American team. So, I privately sent them an email, aiming to improve certain aspects. However, during this process, the email ended up being forwarded back to our Chinese team leader, making them feel extremely awkward as if they were caught speaking ill of others behind their backs. The Chinese leader was not accustomed to providing negative feedback to others. At that moment, I felt both aggrieved because I genuinely wanted to enhance the project and guilty for putting someone I respected in an uncomfortable situation. I believe that if I had discussed the feedback approach with the leader beforehand, perhaps those incidents could have been avoided.

In Erin’s “The Culture Map,” it is highlighted that many European cultures (non UK), such as the French and the Dutch, are known for their directness and strictness when providing negative feedback.

Working in a French company, I have also experienced that many native French individuals do not hesitate to point out issues rather than focus on what has been done well, unlike Americans. Additionally, our company recently acquired a Russian company, and I noticed that our new Russian colleagues also express their dissatisfaction promptly, making it clear and preventing misunderstandings.

In their culture, voicing out negative feedback reflects authenticity. My German colleagues would not hesitate to give low ratings to team members who have not met the standards during year-end evaluations. He believes that if something is not good, there is no need to sugarcoat it. Instead, it is essential to make them truly aware of their situations and motivate them to catch up. I greatly admire this approach, as I personally lack the courage to be as direct. I believe this difference is deeply rooted in my upbringing and my initial experience working for an American company.

One day, I attended a small children’s music concert with a friend. I arrived a bit late, and the concert had already started. I ran into my friend and excitedly exchanged a few words with her (in a very low voice). After the concert, my friend and I volunteered to help clean up the concert area (both of our children performed in it). Suddenly, a woman approached us, pointed her finger at us, and said loudly, “You should be ashamed of yourself, you were speaking while the kids were performing!” She expressed her anger quickly and walked away, leaving us feeling embarrassed and upset. I wasn’t sure if she provided feedback to us in a respectful manner while demanding respect from us.

To be honest, her words made me feel upset for a long time that day, and I kept questioning whether I had shown disrespect to the children. Later, I recalled Erin’s “The Culture Map” and realized that this woman might be from a European country where it is common to exaggerate negative feedback. Perhaps she was hoping that we would improve in the future. Once I understood this, I felt relieved.

If we have a five-point scale for feedback: very poor, poor, average, good, and excellent:

- In the standards of most Americans, you rarely see “very poor” and “poor”. “Average” usually represents poor, “good” represents average, and “excellent” is reserved for truly outstanding performance.

- While for many Europeans, “average” truly means average, it’s not bad and meets the standard requirements. “Good” and “excellent” are reserved for those who have truly outstanding and exceptional behavior.

- In Asian countries like China, Japan, and Korea, the standards among peers may be similar to those of Americans, where it’s rare to provide direct negative feedback. However, the dynamics might be very different between superiors and subordinates, where feedback may be more direct and critical.

I recall when I bought a car in the United States, the director from the dealership requested us to provide them a 100% satisfaction score in their survey. If it’s only 90%, that meant not meeting expectation. This was too extreme in my opinion, 100% means strongly beyond expectation. But I felt what I experienced was good, but not that good yet. However, considering the evaluation criteria in the United States, I reluctantly accepted it.

Understanding that everyone has different views on negative feedback, we can easily find some strategies here to communicate effectively:

If you come from a country where direct feedback is more common, when giving suggestions, you can:

- Explain to others how feedback is understood in your culture (for example, as a means of personal growth).

- Inform them of your feedback standards, as what you consider “good” may be perceived as “very good” in their culture.

- Mix negative feedback with positive feedback.

If you come from a country where indirect feedback is more common, when giving suggestions, you can:

- Be more straightforward in expressing your feedback, as otherwise, others may not grasp the point you are trying to make.

If you also enjoyed this article on cross-cultural communication, I would appreciate your help in completing a brief survey at the end.

Thank you!

Lastly, I originally wrote this article in Chinese, and used ChatGPT to translate most of the contents into English, it’s truly efficient!

Leave a comment