Related post: Cultural Differences In Communication

Related post: How to build trust in different cultures

Recently my company is undergoing a transformation and plans to launch a new ToB product. The department head introduced the products that would be launched in the next quarter, even though the product was not yet fully developed. I believe one specific feature would be our main differentiator from competitors. To prepare for a successful launch in the future, our team carefully studied this feature and provided training to the US sales team, explaining the logic and principles behind this data product, hoping that everyone could better explain our unique selling proposition to clients.

After the training, I asked for feedback from everyone, and one feedback surprised me. The feedback was that, since our product is premature, it was too early to talk about it without actual example, which is a waste of everyone’s time (this was expressed subtly). Although I understood the importance of timing, I was amazed by the practicality of Americans.

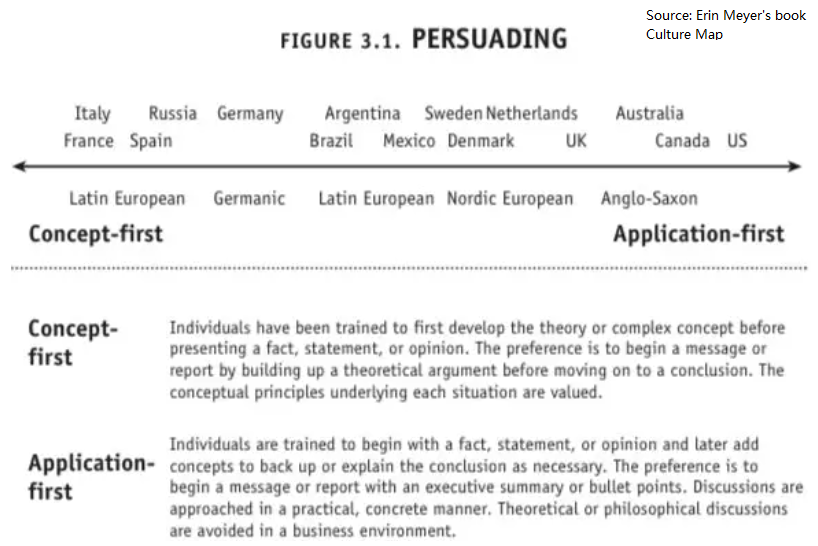

This reminded me of Erin Meyer’s book “The Culture Map,” where she explains that different cultures have different persuasive styles: application-based and principle-based.

- Application-based cultures tend to listen to the conclusions first and then the theory behind it. The emphasis is on how to do things, and it’s not necessarily important to understand the theory behind it. They focus on how to do things.

- Principle-based cultures tend to understand the background and theory first before discussing practical applications. If you only hear the conclusion at the beginning without understanding how it came from, it is difficult to convince people. They focus on why things should be done.

On the scale above, it is easy to see that the United States is on very application-based end, while many European countries, such as Germany, France, and Italy, are on the theoretical end. Although most Asian countries do not appear on this scale, I think that overall we tend to be in the middle, being more practical than European countries such as Germany and France, and more theoretical than the United States. I have many examples through my past 11 years of professional experiences.

My first French boss

I particularly remember my first French boss when I worked in Singapore. On my first day of work, he printed out dozens of pages of company policies and asked me to read them one by one. (I fell asleep reading them on a chair that afternoon…sorry, this is a bit off-topic.) He was a role model for following company rules, and he would ask me to strictly follow the company’s policies and do the right thing too. When I became a manager later, I found that I had been influenced by him in some way. I would ask my colleagues to follow the rules and avoid future troubles (I didn’t ask them to read company policies though).

When we were creating data products, my French boss often emphasized sustainability. We tried to build robust and reliable solutions for the long term. As a result, my project was slow as I had to understand everything, validate and get review from others, with proper code and documentation. In the end, other teams had done a few projects and results were applied in business, but I hadn’t finished one. By the time I finished one project, the momentum was gone. To be honest, I didn’t even know if the final analysis had been used by the commercial team at all, which made me feel discouraged.

Later, when I switched to another project team, the Asian team was much more practical. They were actively rushing to meet deadlines, even if the results were not robust yet. They completed many projects in one year and helped other teams make decisions in a timely manner. Of course, some teams may have done things that were not so reliable, which also led to other troubles and were questioned by more rigorous European teams. That’s a different story though.

Troubles of German Colleagues

Similar things happened in another company too. My German colleagues (internal consulting team) complained to me that it was difficult for new members to establish partnership with other departments, to adopt our recommendations because the new members did not understand the industry. When trying to persuade others, they could not connect the dots from end to end, so others did not believe our results.

To improve this situation, my diligent German colleagues wrote a book, putting all the concepts related to the industry into different chapters, and putting various resources together to help everyone understand the history of the industry in detail. When new people joined, the first thing they do was to have a wholistic understanding of all the concepts from the industry in the book. This project was highly appreciated by our European colleagues, and the analysts had a much better understanding of the business, which made it easier to convince the sales team to use our recommendations because we know our stuff.

However, when the same approach was introduced to some Asian team members (Chinse and Indians), I heard a very different feedback. Many people told me, “I will forget these things if I don’t use them, so why don’t you give me some practical problems to solve first?” “Hey I’ve spent 1 month learning and I’m not doing any actual work, it made me feel panic.”

Compared to many European countries such as Germany and France, most Americans and Chinese focus more on practical applications, and it doesn’t matter much if they do not understand the underlying principles. I have also heard American colleagues complain that European teams are relatively slow to make progress and take risks. They feel that if you have to learn everything in detail before you can use it, it is a waste of time. They believe to just learn the minimum and use it. Moreover, things change so fast now and might become obsolete if we don’t have a fast turnover time. However, European teams can easily argue back. If you do not understand the principles, how can you create a reliable and robust product? How do you know that your analysis is not full of errors?

This reminded me of a US friend who I worked with, he wanted to build a new IT product. He had a business background, with an interest in coding (never systematically before). Without understanding any coding logic, he put together an IT product with the help of ChatGPT, leveraging his ability of “knowing a little bit about everything”. I was really amazed at this. Sometimes I think that this application-oriented culture may be one of the reasons why the number of American entrepreneurs is much higher than other places.

Schools and communities are the same. In Asian countries, most children have to practice music or sports for a long time before performing on stage or participating in competitions. In the US, my third-grade son just started learning basketball, and the teams started matches every week; there were formal coaches and scorekeepers (parent volunteers), they played in an indoor basketball court with huge display screens showing real-time scores, and the audience seats were always full of parents. The school also held talent shows or drama performances every year, even if the children’s skills were very ordinary yet; the school, community, and parents created many opportunities for the children to apply what they had learned as soon as possible.

My Chinese piano teacher told me that she teaches children to play the piano with an emphasize on music foundation (reading the musical notes); she believes that only by laying a good foundation can children truly learn the piano well in the future. On the other hand, American piano teachers focus on the playing and enjoying, it’s not so important if they don’t want to read the notes, and they encourage children to perform even if they’re not good enough. This also deeply impressed me and helped me see the difference too. (Compared to American culture, Asian culture also pays more attention to building the theory and foundation, and you can tell this by the number of exams that each Chinese/Korean student needs to take regularly. )

Cultural Integration

Of course, Americans have a practical approach that Europeans may not always agree with. I remember several times when the American team sent product requests to the French product team, with estimates of how much revenue these improvements might generate. If they didn’t share more background, explain how the revenue was calculated, most of the product requests might quietly stay in the long backlogs without being processed. Even if you tell them that doing this can bring a big amount in revenue, but if they don’t know how you came up with the number, they won’t know if your numbers are credible, and you won’t be able to convince them to help you. So working with the French and Germans, explaining the background and how the conclusions were reached in detail, can greatly enhance your credibility.

I also heard the Math faculty of many French universities is very famous, and very difficult to get in too. When proving certain theories, you may have to prove them in two ways to arrive at a reliable conclusion. My French colleagues, as I recall, take pride in their engineering backgrounds.

When I try to persuade my French boss, he always tried to find situations where my proposal might not work, which looks like he’s arguing with me, but he’s actually helping me prove that my proposal is solid. At first, I was a little uncomfortable with why he always picked faults, but after getting used to it, I found that after arguing with him, my arguments were more reliable and more convincing to others.

Why are these cultural differences?

Erin Meyer mentioned that these differences may be related to Europe’s early industrialization. The assembly line operation led everyone to specialize in certain areas. In contrast, the brief history of the United States allowed many people to directly stand on the shoulders of giants. Many new innovation allowed people to use new products without knowing how they worked behind the scene.

What strategies can you use?

- If you come from a relatively more application-oriented country, you can spend more time explaining the background, why these things need to be done, and explain more specific theoretical foundations instead of just the conclusions.

- If you come from a relatively theoretical country, when persuading others, you can abandon some details and focus more on the future application and how to do it. Directly show your conclusions and results can be very helpful too.

- And when you need to persuade a group of people from mixed culture, you can also toggle between principles and practical examples to keep everyone engaged.

Of course, the most important thing to persuade others is to establish a trust relationship. The way people establish trust is very different in different cultures. I described them a lot more in this article.

If you also like this article, please help me with a quick survey.

Leave a reply to How to build trust in different cultures? – A Growing Me Cancel reply